There are a number of intriguing mysteries that surround the loss of the Steam Ship Mohegan on Cornwall’s Manacle Reef in October 1898 that no one, as yet, has managed to satisfactorily explain any of them.

The Manacle Reef has sunk many fine ships and claimed many thousands of lives, but the story of the Mohegan is a very sad one for a number of reasons, the first of which is, why was the ship set on a collision course with the reef, and why did the captain and crew never seem to have realized the danger until it was much too late.

In those days, ships entering the English Channel from the Atlantic, bound for Falmouth or beyond, may have been at sea for months and be unsure of their correct position, or be compromised by fog or gales. Consequently, as they entered the part of the English Channel where the Lizard peninsular narrows their safe passage and if they were just a little too far north, then they could so easily come to grief on the rocky granite cliffs of Cornwall or the Manacle Reef.

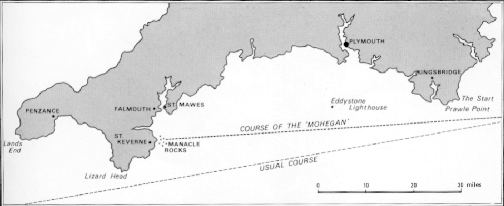

However, the Mohegan wasn’t entering the channel after months at sea and unsure of her position, neither was there fog or storm, in fact, the evening was dark but clear, with lights onshore clearly visible from seaward and the ship was not approaching from the west but running down channel, from the east. The Mohegan was outward bound from Gravesend, bound for New York and had already successfully navigated the narrowest, most crowded, part of the channel and should have been on a safe course for America. However, it seems, that after passing the Eddystone Lighthouse the course was mysteriously changed, in a mistake or a deliberate act, which set the ship on a more northerly, fatal rendezvous with the Manacle Reef.

At the court of inquiry, ordered by the British Board of Trade, it was suggested that the known magnetic quality of the Manacle rocks had upset the compass, drawing the ship to its doom, but this legendary theory was dismissed when it was established that the course had been set by the Captain and it was the course, not the compass, that was incorrect. The Court’s final decision was that ‘After passing the Eddystone lighthouse the wrong course of ‘west by north was steered’ however, the Court could not offer an explanation as to why the wrong course had been set, and there that mystery remains to this day.

The Mohegan left Gravesend on 13th October 1898, entered the English Channel at Dover and set a course for the new world. She carried 53 passengers and a regular crew of 97. Also, onboard were seven cattlemen, who were to look after the cows and horses it was intended to bring back from America, there was also, as it later transpired, one stowaway on board. The Mohegan’s Captain was Commodore Richard Griffiths, a title he carried as the Atlantic Transport Line’s most senior captain.

At 2.40 pm on the 14th October, the ship was in sight of the signal station, at Prawle Point Devon and made the usual signal ‘All’s well, report me’ and later that day was seen off Rame Head signal station, no signals were exchanged before the ship disappeared into a shower of rain, apparently on course for America. Had the Mohegan kept to her course she would have passed ten to twelve nautical miles south of the Manacle Reef. Instead, at some point, her course was changed to ‘west by north’ heading her for the one group of rocks in the whole of the British Isles, that seafarers feared the most. On that course even if she had avoided the Manacles, she would have struck Cornwall’s granite cliffs between Godrevy Cove and Lowland Point, on the Lizard Peninsular.

Around 6.30pm as the Mohegan approached the land, the dinner gong sounded and the elegantly dressed passengers began assembling in the dining saloon, where white-coated stewards were waiting to serve the meal. Commodore Griffiths was on the bridge, the engine room telegraph was set at ‘full ahead’ giving a speed of 15 knots at engine revolutions of 68 rpm. The course was still set at ‘west by north’ with the Manacle Reef dead ahead at less than two miles, so the scene was set for disaster, but all on board seemed to be completely unaware of the danger, even though lights could be seen on the shore.

However, onshore a number of people were becoming aware that the approaching vessel was too close in and headed for disaster. One of the first to spot trouble was Mr. John May, who was the duty Coastguard Officer at Coverack and he acted immediately by going outside and firing off some signal rockets as a warning but received no reply from the ship. Realizing that a disaster was imminent he called out the Rocket Brigade and sent them to the cliff tops at Godrevy Cove, with their equipment, as that appeared to be where the vessel was headed.

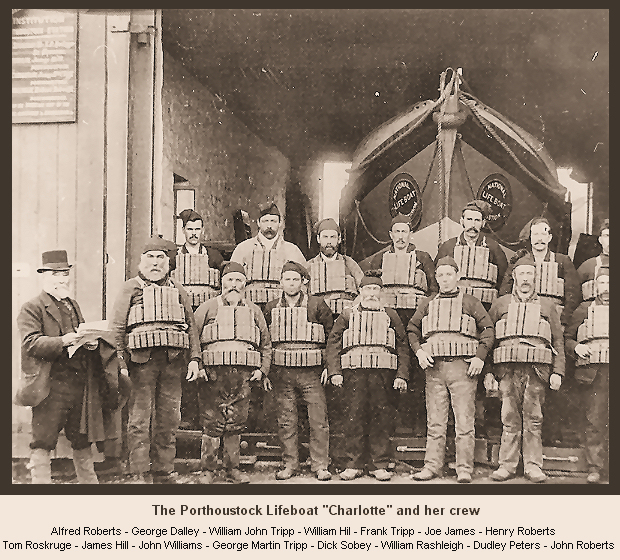

Mr. May was not the only person onshore to realize that the big ship, lit up like a small city, now approaching the land, was headed for disaster. Mr. James Hill, the Cox’n of the Porthoustock lifeboat was standing by his stable door, after putting his horse away for the night when he looked out to sea and was amazed to see a large vessel, heading at speed for the shore. At first, he thought it must be the small steam packet, on her regular run from Falmouth, as no other vessel had any right to be so close inshore. As soon as he realized what was going to happen, he got his horse out and riding bare-back, galloped down to the Lifeboat House and fired off the maroon signal rockets to summon the crew, so within 25 minutes the Porthoustock lifeboat Charlotte was on its way to the Manacles under oars.

At the very last minute the crew onboard the Mohegan seemed to have become aware of the danger and put the wheel over, observers on shore saw the configuration of her lights change, indicating she was altering course, turning to port and on to a more southerly heading. Unfortunately, she turned right into the center of the Manacle Reef, if she had not turned, she may have fared better and hit the cliffs at Godrevy Cove where the Rocket Brigade were waiting and could have reached them with their life-line throwing apparatus, sadly the Manacles was beyond their reach. The time was 6.50 pm.

The impact with the rocks was quite light and no one at first suspected that the ship had been mortally wounded below the waterline, by the razor-sharp rocks, but within two minutes of striking the ship had 14 feet of water in the engine room, submerging the dynamos and one by one, all the lights went out.

The captain acted immediately and ordered all the lifeboats got out, but because of the increasing port list, the starboard boats could not be lowered, so he ordered all the women and children into the port-side boats. However, when the crew tried to hoist the boats up, they proved too heavy, so all the frightened and panicky passengers had to be coaxed out before the boats could be hoisted up and out, where the women and children could re-enter them. All this took time and time was something the Mohegan did not have.

Within 15 minutes of the ship striking the rocks, she sank, with only her funnel and masts above the water. The time was 7.05 pm. As the ship slipped under the water all the starboard lifeboats and one on the port side were still firmly lashed in their chocks. Some people made for the rigging of the masts and Captain Griffith’s last words were reported as being, “get the women into the rigging.” Shortly after this, the wing of the bridge he was standing on slipped beneath the waves and the Commodore of the Atlantic Transport Line was presumed to have gone down with his ship. Three months later a headless body was washed up at Caernarron Bay and identified as Commodore Griffiths. However, before this body turned up, a rumour had spread around that was still strongly held by the older people of St. Kevern community in the 60s, when I was enquiring about the wreck, that Commodore Griffiths survived the sinking, landed at St. Kevern in the Charlotte, then ran off into the night and went into hiding. Curiously, that rumour was also intertwined with another, that the Commodore had deliberately wrecked his own ship because of, either, some dispute with the Atlantic Transport Line or, ‘curiouser and curiouser’, in order to gain some financial advantage from insurance. I never found any good proof offered to substantiate any of this, so it’s just more Mohegan mysteries that we shall probably never discover the truth of.

As I discovered more of the tragedy, I learned that the Porthoustock, lifeboat Charlotte, was attracted by a woman’s screams and quickly came upon an over-turned ships lifeboat and after turning it right way up managed, with some difficulty to rescue two men and also the woman who had been screaming, Miss Rodenbusch and a Mrs. Compton-Swift, They then went on in search of the shipwreck, but almost immediately found a second lifeboat with 24 women and children aboard. That boat had been badly damaged and was in danger of sinking, so James Hill took the survivors on board the Charlotte and, crowded to capacity, headed back passed the Shark’s Fin Rock, to Porthoustock, all the time burning white flares as a signal they needed the assistance of other lifeboats.

When Cox’n James Hill had called the lifeboat crew by firing off maroons, Second Cox’n John Cliff was on the road, returning from St. Kevern, and arrived too late to join the lifeboat crew. Disappointed but undeterred, he rode his horse several miles along the cliff tops above Godrevy Cove where the Rocket Brigade told him that they had heard cries for help, but that the distance was well beyond the range of there apparatus. John Cliff then rode back to Porthoustock where he collected four local men and rowed out in a 14-foot boat to where he estimated the shipwreck was. When they came abreast of the Carn-du rocks, they heard cries for help about a quarter of a mile to the west. Cautiously they pulled towards the rocks with the ancient Cornish name of Maen Varses, where they could see through the darkness, white foam breaking and could just make out the masts and funnel of the wreck. They could see and hear survivors on the funnel and in the rigging but could not reach them or even attract their attention. The ever-resourceful John Cliff took off his necktie soaked it in paraffin, tied it to an oar and set it alight. The survivors saw the flames and John Cliff was able to explain to them that their ship was now resting on the bottom and would sink no further. Also, if they could only hang on, help would soon be coming now that the location of the wreck was known.

In fact, help was on its way from all quarters. The tug Penguin came around the point towing the Falmouth lifeboat and by chance picked up the Head Cattleman, George Maule who had been clinging to a piece of wreckage and had drifted many miles from the wreck. The lifeboat from Cadgewith and another from Polpeor Cove had also arrived but in the darkness failed to spot the masts and funnel amongst the rocks. However, John Cliff, in his small boat returned to Porthoustock and met up with the Charlotte and was able to report the exact position of the wreck before taking up his rightful position in the lifeboat as Second Cox’n, ready for the second mission.

Previously as the Charlotte reached the beach at Porthoustock to unload the 28 survivors, a little incident occurred, that many people noticed but paid scant attention to at the time. A man jumped from the lifeboat and ran up into the village and disappeared. Later it would be claimed that the man was the Mohegan’s, Captain Richard Griffiths.

Quickly the Charlotte set out once more on the second mission of mercy, but as they neared the Mohegan, they found it impossible to bring the lifeboat close enough to the wreck to take off the survivors. The problem was that on the one side were the Maen Varses, and on the other were the boat davits and stanchions of the wreck, sticking up out of the water just waiting to snag the Charlotte. Cox’n James Hill ordered the Bowman to drop their anchor, and then allowed the lifeboat to slowly back down towards the wreck, but even then, they were not quite close enough and daren’t go closer. However, at that point, one of the survivors in the rigging plunged into the sea and swam to the Charlotte. The man was Colin Juddery the Quartermaster of the Mohegan, and a man of great determination, who then swam back to the wreck with a line that could be rigged to rescue the survivors from their precarious perch in the rigging. One by one the survivors were hauled across to the Charlotte, the first to be rescued was a young stewardess and the last was the gallant but exhausted Colin Juddery.

Only 45 of the 158 souls on board survived, the others, including the unfortunate stowaway, either drowned or died of exposure and exhaustion in the rigging or in the cold Cornish sea. Most of the victims were buried in a common grave in St, Kevern churchyard, marked by a simple granite cross, engraved with the legend ‘Mohegan 1898.’

In the early 60s, I was a Navy diver stationed in Cornwall and a very keen wreck diver, but in those far off days before computers and the internet it was quite difficult to obtain accurate, reliable information about shipwrecks and the Mohegan at that time was just, an almost forgotten, bit of Cornish history with the only really known, sure fact, a grave marker in St. Kevern’s churchyard. Then I met old Tommy Hocking, who occasionally drank in my local pub the Hellzepheron, at Gunwalloe. Tommy claimed that as a young lad living in St. Kevern, he had made up the numbers in the lifeboat that night on the first trip out to the Mohegan. At the time Tommy was in his 70s and could have been just old enough, and certainly knew a great deal about the events of that night from the perspective of someone who was involved, but the thought did cross my mind that Tommy was just recounting a bit of Cornish history and writing himself into the script.

One evening after I had bought him a couple of beers to loosen his tongue and jog his memory, he recounted a very interesting episode that I felt must be authentic. He said that as the lifeboat was heading towards the Manacles where they thought the wreck was, they heard a woman screaming, that led them to an overturned ship’s lifeboat with two men clinging to it and the screaming was coming from underneath the boat. They quickly pulled the two men on board and turned the boat right way up which revealed the woman who had been screaming, several bodies and a strange tangled bundle of clothing, hair, and limbs which in the dark appeared to be a dead woman. The bowman said, according to Tommy, “she’s dead leave her” when, to the amazement of all, the ‘dead woman’ cried “I’m not dead, please don’t leave me, save me, I’m trapped by my hair.” Then Tommy jumped down into the waterlogged boat and found that the woman’s very long hair was tangled around one of the thwarts or cross seats. Someone in the lifeboat handed Tommy an axe and with one expert stroke he severed the woman’s hair close to her scalp and without further ado, she was pulled aboard the Charlotte. Tommy further claimed that the woman had then taken an expensive ruby ring from her finger and gave it to him in gratitude for saving her and not leaving her to die. It was a really good story but sounded just a bit too good to be true and at the time I chose to doubt that part of the tale. So, sometime later when I had the opportunity to study the records of the Royal National Lifeboat Institute, I was quite surprised to discover that the incident actually had occurred, with one very small variation. In the records, the man swinging the axe was not Tommy Hocking, but a lifeboatman called Francis Tripp, one of three Tripp relations of father and two sons, manning the lifeboat that night.

The woman who had been screaming from under the boat was a young American opera singer called Miss Rodenbusch, whose trained voice had penetrated the overturned boat, and attracted attention. The woman who had been trapped by her hair was Mrs. Compton-Swift, and her story was quite ironic. She had just recovered from a serious illness and was embarking on the first leg of a world trip, accompanied by her personal physician, Doctor Fallows to try to recover her health. Mrs. Compton-Swift survived the shipwreck but Doctor Fallows was drowned. In the records, there was no mention of her wearing or giving anyone a ruby ring, although this could well have been a very natural gesture from a woman of wealth to a young lifeboatman who, it could be said, had risked his life to save hers.

The Royal Navy had no interest in the wreck of the Mohegan, so if I wanted to dive on her, I would have to organize my own expedition in collaboration with another wreck diving enthusiast friend of mine called George Hedley. However, we needed some local knowledge of the diving conditions on the Manacles, preferably from someone who owned, or had access to, a suitable boat. After phoning around for a while, I found the perfect man. His name was Graham and claimed to be the past Secretary of the St. Kevern Subaqua Club and owned his own boat, looking back I think it was that Graham had his own boat that persuaded me he was the right man for the job, but with hindsight, it became clear I should have spent more effort enquiring into his diving ability. George and I met Graham in the pub and he talked knowledgeably about the Mohegan wreck, the Manacles, the weather and sea conditions and numerous other wrecks he claimed to have dived. Both George and I were impressed at how much he knew about the tides and currents around the wreck and were convinced he had gained his knowledge from long-time diving the area, but, as it was to prove, we were wrong.

We made three attempts to get out on the wreck but each time the weather turned against us, however on our fourth try the weather was absolutely perfect but George was in the naval sick-bay with suspected appendicitis, so Graham and I went out in his boat together. We anchored above the wreck, donned our diving gear and splashed in. My first brief impression of the wreck was of a very large ship, mostly collapsed down to seaward with the huge boilers dominating the site. The only mast now visible, lay across what had once been the cargo hatch and the whole scene was quite melancholy and sad as if the pain of those who had died still lingered in the remains of the once-proud ship. I shook myself, to clear my mind of the negative feeling and turned to ensure Graham was okay.

I was becoming aware that Graham was not quite the brilliant diver he’d led us to believe, he kept rolling around and adjusting his shoulder straps, clearing water from his facemask, with a lot of leg and arm movements, something I found very irritating, I like to remain as still and relaxed as possible underwater so found Grahams jiggling around very distracting. Whilst I was distracted trying to assist Graham, we drifted in the slight current away from the wreck and into a cleft or gully in the rock and it was there that I began to find small artifacts. I picked up a soup plate with a crest, a soup spoon, some other cutlery and what looked like a silver mustard pot. For me, those sorts of items bring back the poignancy of the moment just before the ship struck the rock when everything on board was quite normal, but about to change dramatically forever. Was it, Mrs. Compton-Swift who had just started the soup course? Or was it, Miss Rodenbusch, who was holding the cutlery, or Doctor Fallows who was passing the mustard pot? Quickly I placed the precious items into my sack and turned to check on Graham. It was just at that moment that Graham’s mask filled with water and he began to panic, groping and trashing about, in a desperate attempt to break for the surface. I reached out to try to stop him only to be kicked in the face which dislodged my own mask, filling it with water, so that after clearing it I followed Graham up to the surface.

On the surface, the wind and tide were against us and Graham seemed to be having difficulty, (in those days before buoyancy compensators,) in just staying afloat, so I told him to get his mask on and his mouthpiece in and we would go down on the bottom and swim back to the boat below the effects of the wind and tide. It was then Graham admitted that in his panic to reach the surface he had lost his mask and snorkel, which meant we would have to swim back on the surface, against the increasing wind and mercifully slight tide. I ended up practically towing Graham back to the boat and in the process was obliged to drop my sack with its precious mementos. When we got back to the boat, I was so exhausted that I just could not climb up over the side and was obliged to just hang on and wait until my strength returned.

I felt really angry with myself, as I floated there hanging on to the boat, for accepting Graham at face value and in consequence putting both our lives in peril, but then, as I realized we would both be okay, once I’d regained my strength, my anger dissipated and I began to see the funny side of our, still rather precarious, situation. I had got into this predicament because Graham had told me a load of lies about his abilities as a diver, which I had only too willingly accepted because Graham and his boat suited my purpose. Also, old Tommy Hocking and the lies and half-truths he’d woven into the story of the Mohegan, which had so intrigued me and got me interested in the ship, which once again I had accepted too readily.

As I clung exhausted to the side of the boat, with no chance of mustering enough strength to get aboard, the wind began to rise alarmingly. As the wavelets began to break against the side of the boat and over my exposed head, they made a sound rather like laughter, I couldn’t help but think it was old Tommy Hocking, having the last good laugh at my expense.

I never got another chance to dive the Mohegan, but I did, later, manage to track down one, still living, real hero of the lifeboat that night, Mr. Francis Tripp whom I arranged to meet in his local pub, backed up by a few of his very ancient cronies. He confirmed that it really was him, who had jumped down into the Mohegan’s lifeboat and freed Mrs. Compton-Swift with an axe blow, but then added something that wasn’t in the RNLI records and quite surprised and sadden me. He claimed that as he was attempting to cut Mrs. Compton-Swift’s hair the boat had rolled, unbalancing him and he had fallen sideways, causing his first axe blow to strike the leg of another woman, still alive in the lifeboat, cutting it badly. This woman, Mrs. Lizzie Small Grandin, was gently lifted into the Charlotte, but that sadly, in the darkness, while they were rescuing the people from the second lifeboat, she had become unconscious and quietly bled to death.

Later, when I related to Francis Tripp what Tommy Hocking had told me and how it had got me into such trouble diving with Graham, he and his mates, who knew Tommy, of old laughed out loud. Francis told me that his old friend Tommy Hocking, who they all knew as ‘a teller of tall tales’, had never been to sea in his life and had got the lifeboat story from him when they worked together years before. As to the ruby ring Tommy spoke of, Francis reckoned that it was just one more of Tommy’s made up embellishments, which Tommy was apparently famous for. As I sat listening to Francis Strike and his ancient crony pals laughing at my expense, I had to admit old Tommy Hocking really did have the last laugh.

For a British lifeboat to become newsworthy the crew have usually performed some heroic feat of maritime rescue, or themselves become victims of a violent storm. One lifeboat, however, made a name for itself because of a remarkable journey made on land before it ever reached the sea.

About teatime one January afternoon in 1899 a telegraph message arrived at Lynmouth, North Devon, which said, “about 20 kilometers away, at Porlock, the 19,300-tonne full-rigged ship Forest Hall of Liverpool had anchored offshore. Due to the ferociously raging gale, the ship had dragged her anchors and was now in danger of going aground. This sort of news would normally have prompted the coxswain of the lifeboat to call the crew together and launch their lifeboat, Louisa, to assist and save lives. But the gale was blowing just as strongly at Lynmouth as it was at Porlock, and because of the direction and ferocity of the wind and sea, the launching ramp of the lifeboat house was unapproachable.

When the coxswain tried to telegraph back to Porlock to explain their predicament, he found that he could not get through. The storm was so strong that it had brought the telegraph wires down. Rather than let the Forest Hall weather the night unaided, Coxswain John Crocombe decided on a course of action that had never been attempted before. Indeed, until that moment it had never even been considered possible. They would, he told his crew, transport the Louisa on its carriage to Porlock and launch into the sea there.

Many of the townsfolk who had turned out to help thought it was insane to consider such a difficult task and refused to assist. Fortunately, there were plenty of other men and women with enough courage to try. The first obstacle was to get the lifeboat out of its house while the waves broke over the top. This was achieved by drawing it slowly out of the rear doors and into the street where it was manhandled away from the sea. A local man, Mr. Thomas Jones, then arrived with 16 horses to be hitched to the lifeboat carriage. The long and arduous journey began.

Mr. Moore, the signalman of the lifeboat crew, set off ahead with a gang of willing helpers in a cart drawn by four more of Mr. Jones’s horses. Their job was to dig down banks and fill up ditches to allow passage of the boat on its cumbersome carriage. Once out of town the first big obstacle was the Countisbury Hill, a formidable incline that winds upwards out of Lynton to 300 meters above sea level. The road was very narrow with some huge rocks that were too large to move, and the carriage wheels only just scraped between them with the horses and townspeople pulling and pushing. Then, as they neared the summit, the right, back wheel bashed against a rock and broke the lynchpin that retained it and the wheel fell off. Soaked to the skin and buffeted by the wind that often extinguished their lanterns, the crew managed to repair the damage. They then crested the hill and entered the barren, gale lashed expanse of Exmoor, a most daunting, exposed place to be in winter.

Although they had achieved a great victory against the hill and the weather, they had in fact only traveled three kilometers and at this point, many of the townsfolk lost heart. Exhausted, they returned to Lynmouth. Only 20 remained to face the rest of the journey, including the 13 lifeboat crewmen. Presently, they came across Mr. Moore and his helpers at the entrance to the very narrow Ashton Lane. Only two meters wide in parts, it was far too narrow for the boat on its carriage. Most men would have given up at this point, having done all they possibly could, but the Lynmouth lifeboat crew seemed to have superhuman strength that night. They were determined to get the boat to Porlock, whatever it took.

They knew the carriage was too wide for Ashton Lane, but the carriage and boat together would become bogged down on the soft, rain-soaked surface of Exmoor. They took the boat off its carriage and inched it along the two-kilometer-long lane, pulled by horses and pushed by men, on lengths of wood used as rollers under the keel. The carriage, lighter now without its cargo, was taken across the moor. Eventually, carriage and lifeboat were reunited for the last uphill stage over Hawkcombe Head, 430 meters above the sea. Progress was slow as the crew stopped constantly to clear obstructions. Granite gateposts that had stood for centuries had to be dug around and pushed over, walls were leveled and a large elm tree was felled and cleared from the path of the carriage.

They then faced a whole new set of circumstances as they attempted to descend Porlock Hill, one of England’s steepest. The horses were harnessed at the rear of the carriage for control, and steering had to be done manually, which quickly exhausted the already weary men. When they reached level ground, they had to knock over some walls. An indignant elderly woman looked out of her window to complain about the noise and the destruction of her cottage garden wall. When they told her, they were taking the lifeboat (something she had never seen before) to Porlock to try to save the lives of some sailors, the astonished woman yelled back, ‘Wait for me, I’m coming with you!’ and with one more assistant they set off again.

By the time they reached Porlock the road had been completely washed away. Obliged to take another route, they encountered trees and hedges that had to be cut down before the lifeboat could proceed. Eventually, drenched to the skin and utterly fatigued, they reached Porlock Weir. It was 7 am on Friday the thirteenth, a very bad, in fact, the very worst, omen for the superstitious fishermen.

Their 12-hour ordeal had not proved in vain. The Forest Hall was still afloat just meters from the rocks and the 15 crewmembers were urgently in need of assistance. The lifeboat was launched with 12 men pulling strongly on the oars, at the same moment as a tug came around the point. The two small vessels reached the stricken ship more or less together. The captain of the Forest Hall refused to abandon his ship while there was still a slim chance of saving her and asked if the lifeboat could pass a heavy cable to the tug. Slowly, the tug pulled the sailing ship away from a precarious position near the rocks, with the lifeboat standing-by in case they were unsuccessful or the towline parted.

The ship was leaking badly but the tug captain decided to tow the vessel across the Bristol Channel to Barry in Glamorganshire where there would be shelter from the ferocious weather. The lifeboat was asked to accompany them in case of difficulties and as the crew did not have the strength to row, they threw a line to the Forest Hall and were towed along behind. They reached Barry some 11 hours later, having been either man-handling or rowing the boat for 23 hours without food or hot drink. ‘We were nearly exhausted,’ commented the coxswain, in a brilliant and memorable understatement.

The 13 crewmembers received awards of £5 each and those who had helped to get the boat to Porlock shared 27 pounds, 5 shillings, and sixpence. The total cost of the rescue, including the crew’s reward, the rebuilding of garden walls and the hire of the horses was 118 pounds, seven shillings, and ninepence. The owners of the Forest Hall contributed a miserly £75. Although I personally had a great interest in this incident I could never, of course, have met any of the participants, except, the Forrest Hall who eventually came to grief in NZ waters allowing me to dive on her, although she now lies in shallow water so very little is left of her.

Not all lifeboat stories are tragic or heroic, of course. Many are mundane or routine, and a few are even funny. One particular lifeboat, whose identity is best left unrecorded, had a quite unusual task some years ago. Local fishermen reported to the Lifeboat Institute secretary that a small rowing boat was missing from the beach. A patient from the local lunatic asylum – as it was then known – had recently escaped, and it was surmised that he had stolen the boat and rowed out into what was a considerable south-westerly gale.

Maroon rocket flares were fired and within a short while, all of the crew except one were on board the lifeboat. The coxswain called for a volunteer from the crowd who had gathered to watch, and at once three men stepped forward. The coxswain chose a well-built young man who said he had been a sailor at one time. He was given oilskins and a lifejacket and he took his place in the lifeboat, which proceeded to sea.

The coxswain followed the course that he considered the wind and tide would have taken the stolen boat. They searched all afternoon and into the darkness of evening before admitting that the boat had probably sunk in the tempestuous sea. Determined to renew their efforts first thing in the morning, they returned to the harbour where a crowd, including policemen and two attendants from the asylum, were waiting on the jetty, who the Cox’n told, that it looked very much as if the escaped patient had been unable to control the small boat, been swamped and drowned. Then, as the volunteer crewman removed his sou’wester and lifejacket, the two attendants recognised their missing patient.

‘Come on Ted,’ they said. ‘We’re taking you home.’

‘Ok,’ he replied amiably, ‘but first I’d like to ask the coxswain what it was we were searching for out there.’

‘Well,’ said the coxswain, rather embarrassed, ‘we were looking for someone we thought had stolen a small boat.’ Ted thought about that for a moment.

‘Cor blimey,’ he said, as his attendants led him towards the waiting ambulance. ‘Anyone who would go out in a small boat in this weather must be crazy.’

Another fine blog Roger, I have great admiration for our lifeboat crews and the RNLI.

Our crews on the West Coast of Scotland have many similar tales to tell.

ATB

Mac

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Mac, yeh they do a great job and don’t get paid. Regards Roger.

LikeLiked by 1 person

they that go down to the sea in ships……….great story Roger

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Chas, nice to know you enjoyed it. and if I could just complete your well-chosen quote” “and occupy their business in deep waters, these men see the works of the Lord and his wonders in the deep. All the best Chas and to Baskerville Blond, Jan.

LikeLiked by 1 person